A Meditation on Bohemian Rhapsody

WARNING: This article contains ENDING SPOILERS!!

Back in my student days, I’d played chess competitively and was a two-time national champion, so seeing a session like Bohemian Rhapsody included in the series took Cowboy Bebop to a whole new level of awesome for me. But coming after the epic Jupiter Jazz I and II, this session is often viewed amongst the fandom as a “filler episode”, a jaunt through hippy town with some additional (but not critical) insights on the Bebop universe. In short, it’s taken as a fun romp between the heavier sessions, a story revealing nothing of consequence. And while you can certainly enjoy the session without examining it closely - just as you can enjoy CB as a series without appreciating its litany of references to philosophy, pop culture, and beyond - watching Bohemian Rhapsody can be extremely rewarding if you have the benefit of context, elevating it from mere filler to something more.

So let’s look at this session through the lens of a chess player and see if it sheds any insights on CB as a series. We’ll delve into a few non-chess ideas as well, but let’s start with examining the game of chess and what it has to do with Cowboy Bebop.

What is chess? Chess is essentially a game where one starts out with a mind-boggling array of options* which then, as the game progresses, slowly narrow down to a few possible paths until the game is played to an inevitable conclusion (win/ lose/ draw).

*Note: How many options? At the beginning of a game, before a single move is played, the number of different chess games that can be played is around 10^120 (that's 10 to the power of 120) and that’s the conservative lower bound calculation, known in chess as the Shannon Number. For context, the number of atoms in the observable universe is estimated to be 10^80. In other words, the number of chess games on that 64-square board exceeds the atoms in the observable universe by a few orders of magnitude.

On a thematic level you could argue that Spike’s story plays out like a game of chess. As it started in Asteroid Blues, he was meandering through life onboard the Bebop as a bounty hunter; the syndicate had yet to catch up with him and his life could’ve taken any number of turns, if he’d so wished. Instead, he chose to dwell on his past so as the series progressed, key events took place (eg. The Van ordering anyone connected with Vicious to be hunted down and killed following his failed coup, Jet getting injured in the Loser Bar shootout, Annie and Julia getting killed) which eradicated the possibility of certain paths, forcing Spike to go on the only path that he could imagine taking for himself (ie. Confronting Vicious), which led to its inevitable conclusion.

There’s no indication that this is at all what the CB production team had in mind when they decided to feature chess in a session of the series. For all we know Dai Sato, who's the screenwriter for this session, might’ve pushed to do a chess episode for the fun of it since he himself is a fan of chess. Nonetheless, the parallels between chess and Spike’s story are fun to ponder.

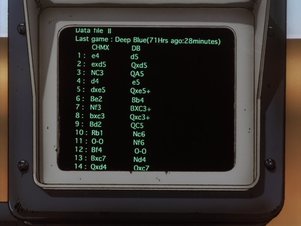

Less speculative are the chess-related Easter Eggs that are embedded in this session. In the scene where Ed tells the rest of the Bebop crew that the King token is actually a memory cartridge, the last game played on the cartridge is loaded and the opponent in this game is shown to be “Deep Blue”. This is, of course, a reference to the IBM-developed chess-playing machine that was the first to beat a human (and it was then-World Champion, Garry Kasparov, no less). Spotting the Deep Blue reference is fun enough for any chess fan, except the Easter Eggs don't just stop there.

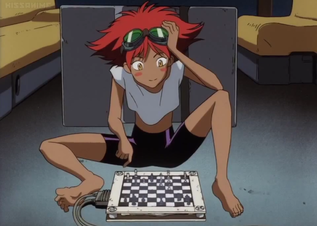

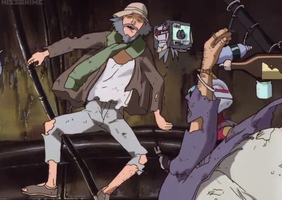

The annotation for this game against Deep Blue is that of a real game played in 1858 between Paul Morphy and Adolf Anderssen, both world class players of the game in their era. Later, when we’re able to get a glimpse of the game between Chessmaster Hex and Ed (image below), we find that it's the board position for yet another real life game.

So let’s look at this session through the lens of a chess player and see if it sheds any insights on CB as a series. We’ll delve into a few non-chess ideas as well, but let’s start with examining the game of chess and what it has to do with Cowboy Bebop.

What is chess? Chess is essentially a game where one starts out with a mind-boggling array of options* which then, as the game progresses, slowly narrow down to a few possible paths until the game is played to an inevitable conclusion (win/ lose/ draw).

*Note: How many options? At the beginning of a game, before a single move is played, the number of different chess games that can be played is around 10^120 (that's 10 to the power of 120) and that’s the conservative lower bound calculation, known in chess as the Shannon Number. For context, the number of atoms in the observable universe is estimated to be 10^80. In other words, the number of chess games on that 64-square board exceeds the atoms in the observable universe by a few orders of magnitude.

On a thematic level you could argue that Spike’s story plays out like a game of chess. As it started in Asteroid Blues, he was meandering through life onboard the Bebop as a bounty hunter; the syndicate had yet to catch up with him and his life could’ve taken any number of turns, if he’d so wished. Instead, he chose to dwell on his past so as the series progressed, key events took place (eg. The Van ordering anyone connected with Vicious to be hunted down and killed following his failed coup, Jet getting injured in the Loser Bar shootout, Annie and Julia getting killed) which eradicated the possibility of certain paths, forcing Spike to go on the only path that he could imagine taking for himself (ie. Confronting Vicious), which led to its inevitable conclusion.

There’s no indication that this is at all what the CB production team had in mind when they decided to feature chess in a session of the series. For all we know Dai Sato, who's the screenwriter for this session, might’ve pushed to do a chess episode for the fun of it since he himself is a fan of chess. Nonetheless, the parallels between chess and Spike’s story are fun to ponder.

Less speculative are the chess-related Easter Eggs that are embedded in this session. In the scene where Ed tells the rest of the Bebop crew that the King token is actually a memory cartridge, the last game played on the cartridge is loaded and the opponent in this game is shown to be “Deep Blue”. This is, of course, a reference to the IBM-developed chess-playing machine that was the first to beat a human (and it was then-World Champion, Garry Kasparov, no less). Spotting the Deep Blue reference is fun enough for any chess fan, except the Easter Eggs don't just stop there.

The annotation for this game against Deep Blue is that of a real game played in 1858 between Paul Morphy and Adolf Anderssen, both world class players of the game in their era. Later, when we’re able to get a glimpse of the game between Chessmaster Hex and Ed (image below), we find that it's the board position for yet another real life game.

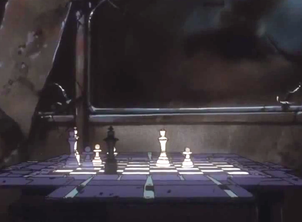

The position shown is drawn from a fairly famous game that took place in 1857 between John William Schulten and Paul Morphy. Some CB fans are perhaps already aware of these facts but what struck me was not that they had made references to real games. After all, the CB production team has a well-established penchant for referencing real life throughout the series; what really struck me as a chess player was that of all the games played through the ages, of all the Grandmasters they could have acknowledged, they chose to reference Paul Morphy, a chess player who had lived over 150 years ago.

In the century and a half since Morphy’s time, there’s been no shortage of brilliant chess games by the likes of Fischer, Capablanca, Kasparov, and Alekhine from which the CB production crew could have drawn reference. So acknowledging Paul Morphy twice in Bohemian Rhapsody is likely deliberate - and the choice all the more fascinating once you understand who this man was in his lifetime and how he is viewed in the world of chess today.

Known as “the Pride and Sorrow of Chess”, Paul Morphy was an eccentric prodigy of the game who had died of a stroke at the age of 47, young even by the standards of his day. At the age of 21, he was already widely recognised as the world champion. But after reaching the pinnacle of the game, he soon gave up playing the game publicly and had bouts of mental instability in the years leading up to his death.

Today, Morphy remains a titan amongst a legion of extraordinary chess players and is still often cited as one of the top 10 players of all time. His games remain extensively studied, which is incredible considering that some truly spectacular minds have advanced the game quite significantly in the century and a half since.

Bobby Fischer himself had once noted that Morphy, if given the time to study modern theory and ideas, had the talent to beat any player in any era. High praise from one of the preeminent players in the history of chess, and a great shame that Morphy was so far ahead of his time that he lacked contemporaries who were able to push his limits as a chess player. We will never know the full extent of his abilities.

So for me, the Morphy references in Bohemian Rhapsody were particularly apt considering that few figures in the annals of chess has had as bittersweet a story as Paul Morphy - quite fitting for a show that is itself rather bittersweet.

Also quite appropriately, the real game between Schulten and Morphy referenced during the Hex and Ed game is not just a random Morphy game that the production team had pulled out of a chess database. It’s a classic Morphy game that exhibits his trademark playing style involving rapid development, brilliant positional play, and sacrifices that round out to a clinical endgame. His games can be works of art, with seemingly innocuous moves that do not seem like much at the time, only revealing their ingenuity later in the game, once we’ve had the benefit of hindsight. Rather like a certain anime series, wouldn't you say?

If I had to guess, screenwriter Dai Sato is probably a fan of Morphy and wanted those two games to be included in Bohemian Rhapsody as an homage to one of the greatest players of the game. That, of course, made it all the more enjoyable for CB fans who do play chess, though some parts did ruffle some feathers. Case in point: the scene in which Ed could have checkmated Hex but then opted for a different move so that they could continue the game. For storytelling purposes, showing Ed being able to checkmate Hex was a quick and easy way to demonstrate her intellect. But in a real game of chess there’s no such thing as an unforeseen one-move checkmate as depicted in that scene, especially not at the level that Hex and Ed are supposed to be playing. Even a semi-competent chess player can spot a checkmate a few moves in advance, so Hex being surprised by the checkmate simply didn’t fly.

In the century and a half since Morphy’s time, there’s been no shortage of brilliant chess games by the likes of Fischer, Capablanca, Kasparov, and Alekhine from which the CB production crew could have drawn reference. So acknowledging Paul Morphy twice in Bohemian Rhapsody is likely deliberate - and the choice all the more fascinating once you understand who this man was in his lifetime and how he is viewed in the world of chess today.

Known as “the Pride and Sorrow of Chess”, Paul Morphy was an eccentric prodigy of the game who had died of a stroke at the age of 47, young even by the standards of his day. At the age of 21, he was already widely recognised as the world champion. But after reaching the pinnacle of the game, he soon gave up playing the game publicly and had bouts of mental instability in the years leading up to his death.

Today, Morphy remains a titan amongst a legion of extraordinary chess players and is still often cited as one of the top 10 players of all time. His games remain extensively studied, which is incredible considering that some truly spectacular minds have advanced the game quite significantly in the century and a half since.

Bobby Fischer himself had once noted that Morphy, if given the time to study modern theory and ideas, had the talent to beat any player in any era. High praise from one of the preeminent players in the history of chess, and a great shame that Morphy was so far ahead of his time that he lacked contemporaries who were able to push his limits as a chess player. We will never know the full extent of his abilities.

So for me, the Morphy references in Bohemian Rhapsody were particularly apt considering that few figures in the annals of chess has had as bittersweet a story as Paul Morphy - quite fitting for a show that is itself rather bittersweet.

Also quite appropriately, the real game between Schulten and Morphy referenced during the Hex and Ed game is not just a random Morphy game that the production team had pulled out of a chess database. It’s a classic Morphy game that exhibits his trademark playing style involving rapid development, brilliant positional play, and sacrifices that round out to a clinical endgame. His games can be works of art, with seemingly innocuous moves that do not seem like much at the time, only revealing their ingenuity later in the game, once we’ve had the benefit of hindsight. Rather like a certain anime series, wouldn't you say?

If I had to guess, screenwriter Dai Sato is probably a fan of Morphy and wanted those two games to be included in Bohemian Rhapsody as an homage to one of the greatest players of the game. That, of course, made it all the more enjoyable for CB fans who do play chess, though some parts did ruffle some feathers. Case in point: the scene in which Ed could have checkmated Hex but then opted for a different move so that they could continue the game. For storytelling purposes, showing Ed being able to checkmate Hex was a quick and easy way to demonstrate her intellect. But in a real game of chess there’s no such thing as an unforeseen one-move checkmate as depicted in that scene, especially not at the level that Hex and Ed are supposed to be playing. Even a semi-competent chess player can spot a checkmate a few moves in advance, so Hex being surprised by the checkmate simply didn’t fly.

Moving beyond chess, one thing that has puzzled me is the broadly held sentiment that Bohemian Rhapsody's storyline has no bearing on the core story (ie. Spike’s). To me the session reads differently, and the point becomes more evident on a re-watch of the series. Consider the story of Chessmaster Hex: a brilliant scientist exacts his vengeance with a plan to be implemented 50 years later, by which time he has gone senile and is in a completely different headspace. More accurately, what had once been a small part of his life (chess) has grown now to encompasses all of it. This begs the question: is he the same man as the one who’d plotted his revenge 5 decades ago? Or can a man appear to have the same identity and yet be completely different?

Now consider the story of Spike: a man so ensnared by a past life that he drifts through his present one, never quite sure whether the events around him are reality or dream. At this point, is he alive and awake? Or can a man appear to be alive and yet not actually living?

Spike himself directly references this idea in the Real Folk Blues II. Recall his famous parting words to Faye as he left the Bebop:

SPIKE:

I'm not going there to die. I'm going there to see if I really am alive.

Later, during his confrontation with Vicious, the idea of being awake/ alive is evoked again:

VICIOUS:

So you are finally awake. I told you before, Spike... that I am the only one who can kill you.

Implicit in his words, of course, is that Spike had not been awake prior. And all of a sudden we’re deep in Ship of Theseus territory, a domain that CB has approached time and again from different angles. For the uninitiated, the Ship of Theseus is basically a thought experiment that asks whether a ship that has had every single one of its original parts replaced can still be considered the same object. If you replace just one plank of wood on the ship, you can easily say "it's the same ship". But what if every piece of wood is replaced? Does the ship still retain its identity as the Ship of Theseus?

Now consider the story of Spike: a man so ensnared by a past life that he drifts through his present one, never quite sure whether the events around him are reality or dream. At this point, is he alive and awake? Or can a man appear to be alive and yet not actually living?

Spike himself directly references this idea in the Real Folk Blues II. Recall his famous parting words to Faye as he left the Bebop:

SPIKE:

I'm not going there to die. I'm going there to see if I really am alive.

Later, during his confrontation with Vicious, the idea of being awake/ alive is evoked again:

VICIOUS:

So you are finally awake. I told you before, Spike... that I am the only one who can kill you.

Implicit in his words, of course, is that Spike had not been awake prior. And all of a sudden we’re deep in Ship of Theseus territory, a domain that CB has approached time and again from different angles. For the uninitiated, the Ship of Theseus is basically a thought experiment that asks whether a ship that has had every single one of its original parts replaced can still be considered the same object. If you replace just one plank of wood on the ship, you can easily say "it's the same ship". But what if every piece of wood is replaced? Does the ship still retain its identity as the Ship of Theseus?

Through Chessmaster Hex, Bohemian Rhapsody poses this question in a different way: can someone who loses all intent and memory of one’s past - which make up so much of one’s sense of self - still retain the same identity? This is a core question of the series that manifests in different characters: is the Faye onboard the Bebop the same person as the one who recorded that video for herself all those years ago? Is the Gren on Callisto the same man who’d fought in the war on Titan? Is Wen, from Sympathy for the Devil, the same boy he resembles pre-Gate Accident? Through central and minor characters, CB repeatedly forces us to consider our ideas of “identity” and “existence” and how form and substance influence identity.

Put another way, if Faye, Gren, Wen, and Hex are all different people from their previous selves because they are different mentally, then how much of Spike can be considered here, present and awake, when his mind is living in the past? Like so much of CB, the answer isn’t quite black and white or simply spoonfed to us. Rather, we’re left to draw our own conclusions based on how we interpret different scenes.

Finally, Bohemian Rhapsody breaks the filler mould by telling a story that closely ties in with the theme of nihilism that is ever-present throughout CB. Virtually everything that the characters (major or minor) try to pursue comes to a fruitless end, including bounties, former lovers, memories and (hilariously, on one occasion) when a coffin was ruined just as someone had dragged it to its intended occupant. In fact, there are so many occasions where characters lose something just as they’ve found/obtained it that this should be a CB drinking game.

Put another way, if Faye, Gren, Wen, and Hex are all different people from their previous selves because they are different mentally, then how much of Spike can be considered here, present and awake, when his mind is living in the past? Like so much of CB, the answer isn’t quite black and white or simply spoonfed to us. Rather, we’re left to draw our own conclusions based on how we interpret different scenes.

Finally, Bohemian Rhapsody breaks the filler mould by telling a story that closely ties in with the theme of nihilism that is ever-present throughout CB. Virtually everything that the characters (major or minor) try to pursue comes to a fruitless end, including bounties, former lovers, memories and (hilariously, on one occasion) when a coffin was ruined just as someone had dragged it to its intended occupant. In fact, there are so many occasions where characters lose something just as they’ve found/obtained it that this should be a CB drinking game.

Just in Bohemian Rhapsody alone, the "all that for nothing" counter is going nuts: first we see Spike, Jet, and Faye apprehending hackers who turn out to be no help at all (which then becomes a case of “oh, wait! Here’s a lead!” that leads to… no bounty after all), then we learn that Hex had plotted a devastating revenge but is no longer compos mentis enough to appreciate his own handiwork. Then we have Jonathan confronting Hex, only to realise he’ll never get his life savings back. Meanwhile, the Bebop crew has finally apprehended someone who could provide a windfall but then Jet lets the opportunity slide. And of course Hex dies within a week of Jet’s noble act, leaving Ed without a chess partner yet again.

With Bohemian Rhapsody, we experience yet again the sense of futility that pervades the Bebop crew and, more generally, through CB as a series. It is precisely this sense of "failing all the while trying", this decision to give the characters a less-than-fairytale ending that adds a dose of realism to the story, making Spike and all the other characters that much more relatable. While the session may not be a stand out for most, with its blend of well-chosen Easter Eggs, humour, and meditation on the meaning of identity and life, Bohemian Rhapsody is nonetheless a class act in the masterpiece that is Cowboy Bebop.

[ by Leigh ].

With Bohemian Rhapsody, we experience yet again the sense of futility that pervades the Bebop crew and, more generally, through CB as a series. It is precisely this sense of "failing all the while trying", this decision to give the characters a less-than-fairytale ending that adds a dose of realism to the story, making Spike and all the other characters that much more relatable. While the session may not be a stand out for most, with its blend of well-chosen Easter Eggs, humour, and meditation on the meaning of identity and life, Bohemian Rhapsody is nonetheless a class act in the masterpiece that is Cowboy Bebop.

[ by Leigh ].

Want to share your thoughts on this essay? Join in the discussion in the Comments section:

HTML Comment Box is loading comments...