Real Folk Blues: Reading Between the Lines

WARNING: This article contains ENDING SPOILERS

The ambiguity in Cowboy Bebop is the single greatest curse and fortune the creators left for the fans. The mystery surrounding the characters' past, the "misfit" session Boogie Woogie and what really happened in Toys in the Attic can virtually be taken in any conceivable direction-- so much so that fans are seldom on the same page with regards to important points. Which is Spike's fake eye? What is Faye's maiden last name? And does Spike really die in the end??

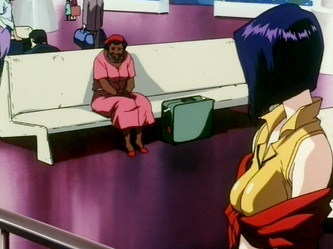

For all their deliberate ambiguity on various issues, the creators of Cowboy Bebop are surprisingly clear on one thing-- that Spike does die in the Real Folk Blues (RFB). Indeed, every scene in the RFB (including that spaceport meeting between Punch/Alfred and mother) appears to proffer a unifying explanation for Spike's decision to leave the Bebop in the end.

For all their deliberate ambiguity on various issues, the creators of Cowboy Bebop are surprisingly clear on one thing-- that Spike does die in the Real Folk Blues (RFB). Indeed, every scene in the RFB (including that spaceport meeting between Punch/Alfred and mother) appears to proffer a unifying explanation for Spike's decision to leave the Bebop in the end.

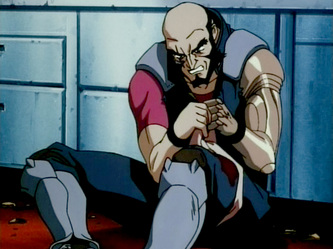

Recall the shootout in Loser's Bar in RFB I. The syndicate comes knocking on Spike's door; it's time for him to repay his debts for no one ever lives to leave a syndicate. But why is it Jet, and not Spike, who gets the "punishment"? At first glance, the shot at Jet appears purely accidental. However, if you know your Cowboy Bebop you would know that nothing is merely "accidental" in this series. Could this incident possibly have more to do with the creators' deeper intentions than random theatrics?

Consider: Jet is shot in the left leg and an injury in a shootout isn't all too surprising. They are bounty hunters -- danger is the name of the game and Jet is certainly not taking a bullet for the first time. What is odd, though, is the way the subsequent scenes made such a big deal out of this wound. First there is the whole tedious business of taking the bullet out at the doctor's clinic. Up until now, the series had never made a big deal out of even the most devastating wounds sustained by the Bebop crew. As an extreme case in point: in Ballad of Fallen Angels, after Spike's tremendous fall from the church window the story simply cuts to him safely onboard the Bebop, bandaged and conscious. In other words, where Cowboy Bebop is concerned, recovery is presumed and taken for granted.

After the Loser's Bar shootout, however, we are uncharacteristically treated to a full display of Bullet Injury 101. Jet's muffled growls and groans are contrasted by Spike's muted disquiet. Note that by now we have also gotten a number of close ups of Spike. From the look of determination on his face as he hauls Jet out of Loser's Bar to the contemplative gaze out the clinic window to the close up on his eyes in the same scene to his gazing out into space as they fly over Mars, it does begin to look like something is troubling Spike.

Consider: Jet is shot in the left leg and an injury in a shootout isn't all too surprising. They are bounty hunters -- danger is the name of the game and Jet is certainly not taking a bullet for the first time. What is odd, though, is the way the subsequent scenes made such a big deal out of this wound. First there is the whole tedious business of taking the bullet out at the doctor's clinic. Up until now, the series had never made a big deal out of even the most devastating wounds sustained by the Bebop crew. As an extreme case in point: in Ballad of Fallen Angels, after Spike's tremendous fall from the church window the story simply cuts to him safely onboard the Bebop, bandaged and conscious. In other words, where Cowboy Bebop is concerned, recovery is presumed and taken for granted.

After the Loser's Bar shootout, however, we are uncharacteristically treated to a full display of Bullet Injury 101. Jet's muffled growls and groans are contrasted by Spike's muted disquiet. Note that by now we have also gotten a number of close ups of Spike. From the look of determination on his face as he hauls Jet out of Loser's Bar to the contemplative gaze out the clinic window to the close up on his eyes in the same scene to his gazing out into space as they fly over Mars, it does begin to look like something is troubling Spike.

As the Bebop flies over Mars, we are again reminded that Jet has taken a bad, bad shot. He limps conspicuously across the screen and his injured leg (with the entire thigh bandaged, no less!) is paraded around in all its crutch-worthy glory. Now I've never taken a bullet before so it is difficult to judge, but that still seems like a lot of bandage for a hole in the flesh.

The first words out of Spike's mouth are also rather uncharacteristic, "Does it still hurt?" Jet is no weakling who requires Spike's constant watch; he is an equal, a comrade in battle. Spike's concern here for Jet seems just slightly out of place and one begins to wonder whether he is taking Jet's injury personally.

The deliberate attack on Annie is an extension of this idea; notice that Spike only ostensibly decides to confront the syndicate immediately after finding Annie in her wrecked shop. Spike is an individualist, as is everyone on board the Bebop. His past is his alone to deal with. That others would be embroiled in its violent mess, I imagine, would eat into his conscience to a certain degree.

In this light, it wouldn't be too much of a stretch to think that, much as Spike left to face Vicious because he knew it was time to come to terms with his own past, Spike was also leaving in part for the safety of the Bebop crew. Rather than waiting for the syndicate to come after him, he took the offensive and dealt with his past on his own terms. He distances himself from Jet and Faye so that he will no longer become a liability to them. The meeting between Punch/Alfred and mother which Faye witnessed seems to point towards this idea.*

The deliberate attack on Annie is an extension of this idea; notice that Spike only ostensibly decides to confront the syndicate immediately after finding Annie in her wrecked shop. Spike is an individualist, as is everyone on board the Bebop. His past is his alone to deal with. That others would be embroiled in its violent mess, I imagine, would eat into his conscience to a certain degree.

In this light, it wouldn't be too much of a stretch to think that, much as Spike left to face Vicious because he knew it was time to come to terms with his own past, Spike was also leaving in part for the safety of the Bebop crew. Rather than waiting for the syndicate to come after him, he took the offensive and dealt with his past on his own terms. He distances himself from Jet and Faye so that he will no longer become a liability to them. The meeting between Punch/Alfred and mother which Faye witnessed seems to point towards this idea.*

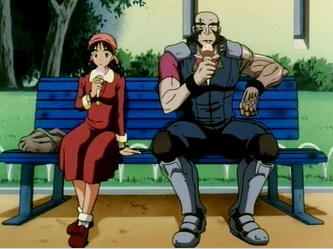

*For those missed out, the man who comes to pick up his mother bears an uncanny resemblance to Big Shot's host, Punch. His mother calls him Alfred and asks about his female co-host. There is no doubt in my mind that she is referring to Judy, the blonde co-host of Big Shot. Refer to transcripts.

Faye overhears the old woman's mutterings:

"So there is no place for me after all. I won't go no matter who comes to pick me up. Never. I don't want to live a life where I'm always in someone's way."

Her concerns here are clear -- she doesn't want to live beholden to anyone and this is an interesting parallel to Spike's situation.

Additionally, CB director Shinichiro Watanabe (SW) highlighted the importance of this scene during an interview session at the 2002 Anime Expo in New York. A transcript:

FAN:

The round up show is canceled near the end of series, but the host is brought into the main story line at the end. Why?

SW:

I didn't want to put him on screen, so she [the screenwriter, Keiko Nobumoto] just went ahead and wrote that scene herself. And she told me this was the most important scene in the episode, so I couldn't cut it.

Very possibly, Nobumoto considered this to be the most important scene because it had a direct bearing on Spike's actions towards the end and, inherently, our understanding of the series as a whole. Furthermore, an interesting exchange between Spike and Jet takes place just as the former prepares to leave the Bebop --

JET:

Is it for the woman?

SPIKE:

There is nothing I can do for a dead woman.

That's a rather curious answer to give. It does not quite answer Jet's question, but it could imply that he is doing it out of consideration for others' safety-- others who still have a future to look towards, i.e. the Bebop crew. Spike does not appear to be suicidally bitter here, but if you insist on taking the "his love is dead and he wants to unite with her in death" tragic-hero line then there isn't much else to discuss. For the sake of the argument, let's assume there is something else-- something more subtle-- that is spurring him on to that final meeting with Vicious. My belief is that Spike was unable to envision a future for himself-- the odd concoction of Past and Present has consumed him irrevocably. In a world where his love is dead and his closest comrade/friend has turned into nemesis, there really doesn't seem to be much left to lose.

So in the interest of himself and others, he leaves.

While Spike is no big softie at heart, he evidently cares for his crewmates. At the very least, he does not want to have their deaths on his conscience. Of course, Vicious would dance the Para Para before Spike actually admits to this.

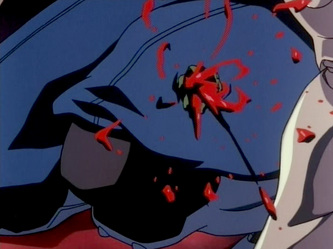

Still, Cowboy Bebop is very much about human ties and how we relate to ourselves and others. That Spike should choose to confront Vicious for himself as well as for others adds that much more to the final message. Spikes must die in the battle against Vicious, if only for the very simple reason that his survival would negate the value of his decision and sacrifice.

Spike must die, not for theatrical purposes but to add to the message that the creators of the series wanted us to see.

For all the gun-toting, bad-ass style that frames much of Cowboy Bebop, the heart of the story is a sincere one. If we fail to understand Spike's choice and fate, then we would have missed out on an important idea, a by-line that appears in the final moment of the entire series:

You're Gonna Carry That Weight.

We're gonna carry that weight-- the weight that is at once the load of our past and also the promise and burden of unrealized hopes and aspirations for the future-- the future Spike never had a chance with. As Shinichiro Watanabe once revealed about this line taken from the last Beatles's album, "The meaning behind that phrase, since the Beatles took a lot of weight from the fans, was that the fans had to now carry that weight."

This short series of 26 sessions has been nothing short of an immaculately conceived dream. The Bebop takes us on a joyride but sends us back with an encouraging lesson: while Spike is no longer able to carry the weight, we, whose lives and dreams continue, can.

In the Real Folk Blues, the troubles of the past and the present converge in one spectacular finale, concluding with an apt ending which suits the dramatic, thematic and philosophical purposes which Cowboy Bebop has always strived towards.

And it is anything but ambiguous.

[by Leigh].

Faye overhears the old woman's mutterings:

"So there is no place for me after all. I won't go no matter who comes to pick me up. Never. I don't want to live a life where I'm always in someone's way."

Her concerns here are clear -- she doesn't want to live beholden to anyone and this is an interesting parallel to Spike's situation.

Additionally, CB director Shinichiro Watanabe (SW) highlighted the importance of this scene during an interview session at the 2002 Anime Expo in New York. A transcript:

FAN:

The round up show is canceled near the end of series, but the host is brought into the main story line at the end. Why?

SW:

I didn't want to put him on screen, so she [the screenwriter, Keiko Nobumoto] just went ahead and wrote that scene herself. And she told me this was the most important scene in the episode, so I couldn't cut it.

Very possibly, Nobumoto considered this to be the most important scene because it had a direct bearing on Spike's actions towards the end and, inherently, our understanding of the series as a whole. Furthermore, an interesting exchange between Spike and Jet takes place just as the former prepares to leave the Bebop --

JET:

Is it for the woman?

SPIKE:

There is nothing I can do for a dead woman.

That's a rather curious answer to give. It does not quite answer Jet's question, but it could imply that he is doing it out of consideration for others' safety-- others who still have a future to look towards, i.e. the Bebop crew. Spike does not appear to be suicidally bitter here, but if you insist on taking the "his love is dead and he wants to unite with her in death" tragic-hero line then there isn't much else to discuss. For the sake of the argument, let's assume there is something else-- something more subtle-- that is spurring him on to that final meeting with Vicious. My belief is that Spike was unable to envision a future for himself-- the odd concoction of Past and Present has consumed him irrevocably. In a world where his love is dead and his closest comrade/friend has turned into nemesis, there really doesn't seem to be much left to lose.

So in the interest of himself and others, he leaves.

While Spike is no big softie at heart, he evidently cares for his crewmates. At the very least, he does not want to have their deaths on his conscience. Of course, Vicious would dance the Para Para before Spike actually admits to this.

Still, Cowboy Bebop is very much about human ties and how we relate to ourselves and others. That Spike should choose to confront Vicious for himself as well as for others adds that much more to the final message. Spikes must die in the battle against Vicious, if only for the very simple reason that his survival would negate the value of his decision and sacrifice.

Spike must die, not for theatrical purposes but to add to the message that the creators of the series wanted us to see.

For all the gun-toting, bad-ass style that frames much of Cowboy Bebop, the heart of the story is a sincere one. If we fail to understand Spike's choice and fate, then we would have missed out on an important idea, a by-line that appears in the final moment of the entire series:

You're Gonna Carry That Weight.

We're gonna carry that weight-- the weight that is at once the load of our past and also the promise and burden of unrealized hopes and aspirations for the future-- the future Spike never had a chance with. As Shinichiro Watanabe once revealed about this line taken from the last Beatles's album, "The meaning behind that phrase, since the Beatles took a lot of weight from the fans, was that the fans had to now carry that weight."

This short series of 26 sessions has been nothing short of an immaculately conceived dream. The Bebop takes us on a joyride but sends us back with an encouraging lesson: while Spike is no longer able to carry the weight, we, whose lives and dreams continue, can.

In the Real Folk Blues, the troubles of the past and the present converge in one spectacular finale, concluding with an apt ending which suits the dramatic, thematic and philosophical purposes which Cowboy Bebop has always strived towards.

And it is anything but ambiguous.

[by Leigh].

Want to share your thoughts on this essay? Join in the discussion in the Comments section:

HTML Comment Box is loading comments...